The class bell rings just in time for Virginia Beach Middle School’s special guests.

Monet’s water lilies need a bathroom break.

Warhol’s pop art is pooped.

Munch wants a break from “screaming.”

And Franz Marc’s blue horse finds a stool and sits.

It’s tough to be a real-life work of art. There’s all that standing and posing and frozen expressions.

Salvador Dali uses the break to add more duct tape to a stuffed cat perched on his shoulder. Gifted visual arts student Leigh Cress (known today as Dali and wearing a flamboyant moustache) explains, “He loved cats.”

“But he was terrified of grasshoppers,” adds Hannah Mancoll, the sixth-grade docent who also researched Dali’s art and introduces Cress as Dali to their museum visitors.

The class bell rings again, signaling the end of the students’ break. Shushing each other as school staff cue them to take their places, Monet, his water lilies and the rest of the gifted visual arts students set themselves for the next hour of tours.

Picasso’s cubist musicians raise their instruments. Van Gogh adjusts a bandage around his ears. Munch resumes his frozen screaming expression. And the American Gothic farmer, with pitchfork in hand, flattens his smile to replicate the iconic scene.

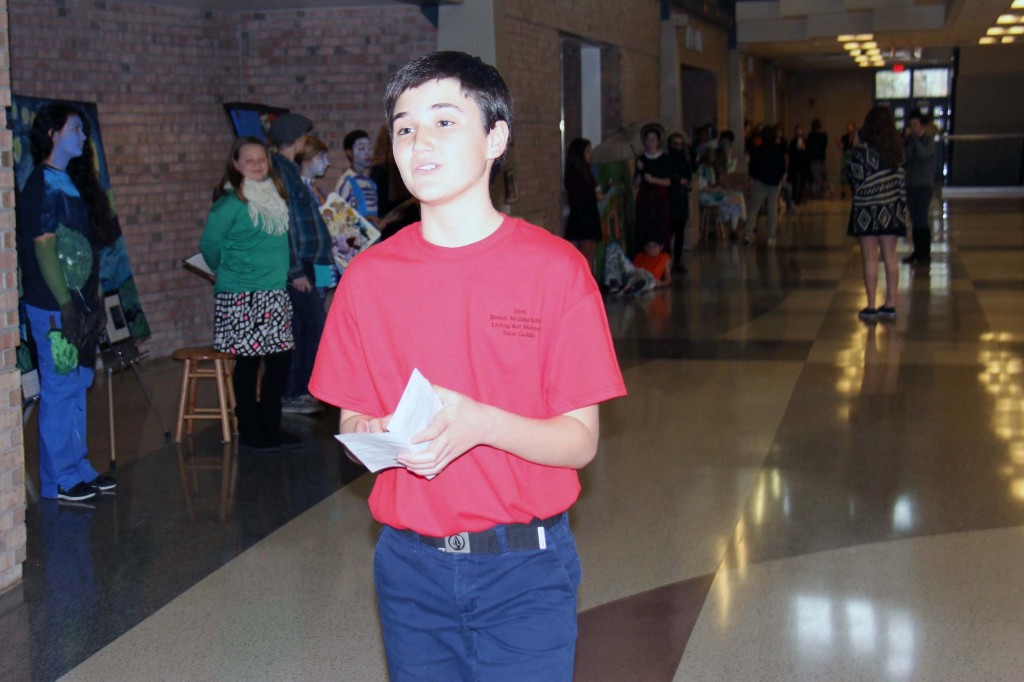

Like an experienced gallery guide, eighth-grader Haiden Daniels talks and walks backward as he leads museum visitors to meet their first artist – Georgia O’Keeffe.

Along the way, the group passes Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, pop artist Roy Lichtenstein and installation artist Sandy Skoglund, whose Cheez-Doodle covered chair and student in The Cocktail Party was a popular attraction.

Daniels assures his guests they may circle back to view any piece of art in the living exhibit after the initial tour.

Dispatching more student guides to lead visitors through the museum is Gifted Visual Arts teacher Jessica Provow. It was her idea to have students replicate famous works of art in wearable form, similar to an event Provow helped coordinate as an art education student at Longwood University.

“We worked with the local museum in Farmville,” Provow explained, “and we brought artists and art educators together to create living works of art. It was a big gala event, so the whole community came.”

Similar to the gala, Provow and her gifted visual arts colleagues Leah Krueger and Leigh Drake, selected famous works of art for groups of students to study and recreate together. Group members had to collaborate and problem solve to bring their ideas to life and then assign roles for the live exhibit.

“They chose whether they wanted to be the artist, the docent or in the artwork,” Provow said. “They did all the research to embody that person and created their own scripts.”

Every student assumed a role and spoke in character to museum visitors, demonstrating their knowledge of the artist, the work’s history or the artistic technique.

“We were looking for a new way to teach the art history and aesthetics in our art theory units,” Kreuger added. The student-centered approach is what helped Kreuger and her colleagues earn a $2,000 innovative learning grant from the Virginia Beach Education Foundation, underwritten by Deford Ltd., to fund this first-time project. “By placing students in this authentic learning situation, they must think like a museum curator as they decide what qualities are important to reflect in the art piece selected for the exhibit,” Kreuger wrote in the grant application.

Kim Urch’s seventh-grade daughter Abbey played the role of Georgia O’Keeffe. As Abbey and her group members explained the history of and technique used in O’Keeffe’s work Oriental Poppies, Kim took photographs of the art in action.

“They have been working on this project for weeks,” Kim said. “Abbey learned more about Georgia O’Keeffe than just her artwork. She learned about her life and what motivated her. Then they had to work together to create an amazing artwork that would come alive. It was impressive to see all of their preparation turned into an amazing display of their talents.”

Daniels and his tour group bid farewell to Ms. O’Keeffe.

Next stop? Paris.

There they find French artist Georges Seurat near the banks of the Seine River on a Sunday afternoon in the late 1800s.

Student docent Alex Riggenbach shared information about Seurat’s life and his pointillism piece A Sunday Afternoon On The Island Of La Grande Jatte. “Let’s chat with George himself,” transitions Riggenbach, and sixth-grader Bella Kane breaks her pose with a flip of her paint brush.

Speaking through a fake moustache and beard, Kane describes Seurat’s pointillism technique in first person. Her accent is part French, part “fancy,” as described by fellow group member Jillian Atwood. Atwood is one of the French fair ladies in the piece, and her monologue is quickly interrupted by the artist himself who says, “Oh, let me add one more dot.”

Kane taps a paintbrush to Atwood’s face and says, in a French-fancy way, “There we go!”

Atwood tries not to laugh and break character.

After their presentation to museum visitors, Riggenbach described her group’s work behind the scenes. “It took us a month to complete this because we had to do a base color and then we had to dot the whole thing.” Much less time than the two years (1884-1886) it took Seurat to complete his famous work.

“I enjoyed learning about the dotting technique,” said Kane. “I think it’s a really cool way to paint. It takes more time to process, but I think it makes it more special.”

Atwood also appreciated Seurat’s pointillism, especially for his time. “I find it very innovative what he did because I don’t think anybody in that time era had done that before,” she said.

Out of character, each student had something to share about what they learned.

“He painted it because he was on a walk with his friends and he saw the sunset,” explained the student docent for Edvard Munch’s The Scream. “He felt so many emotions at once that he wanted to scream, so he decided to paint it instead.”

The student featured in Lichenstein’s comic strip art M-Maybe learned that “he uses a lot of bright colors.” Bright red polka dots covered her face for her to blend in with the piece’s background.

“The dull colors are mostly in the background because he is a pop artist.”

Amaya Dinh, a blue character in Keith Haring’s untitled contemporary work, learned she should have selected a different character in the piece. Unlike the other four characters, it was painted with arms outstretched above its head, a pose she had to hold to replicate Haring’s work.

“I should have been a red character,” she said. “My arms hurt.”

To learn more about how you can support creative and innovative learning programs through the Virginia Beach Education Foundation, visit vbef.org or contact Foundation coordinator Debbie Griffey at (757) 263-1337.

Because I studied Van Gogh and Dali in college, I am intrigued by the presentation of their work. Awesome! to see teenagers mimic their work in such a detailed and delicate way.

Wow, they are doing great things in the Art Department at VBMS!!