Time: Boston, 1770

Event: Boston Massacre, known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street

This historic confrontation between patriot colonists and British soldiers in 1770 on the streets of Boston, Massachusetts, ended with both sides engaged in a propaganda battle to promote their version of events. It was also one of the key incidents that led to the American Revolution. For sixth-grade students at Landstown Middle School, it became a great lesson on using critical thinking skills to learn about different perspectives.

“They didn’t have CSI [crime scene investigators] at that time so it was a mix of opinions of what happened,” said Diane Tarkenton, the school’s gifted teacher who was the main organizer of the mock simulation activity – one of five stations that students rotated through. “I’m hoping they leave with ‘there’s no one right answer’ and that there were two sides.”

At the Boston Massacre station, set up in the school’s main foyer, students first encountered an area blocked off by yellow tape, marking the place where the skirmish took place. Inside the sectioned-off area were sticks and white balls simulating the snowballs hurled that eventful night.

Surrounding the area, students from First Colonial High School’s (FCHS) Legal Studies Academy awaited the sixth-graders.

“The students from First Colonial were a perfect fit because they have community service to do and they know the legal ramifications [of witness testimony],” Tarkenton stated.

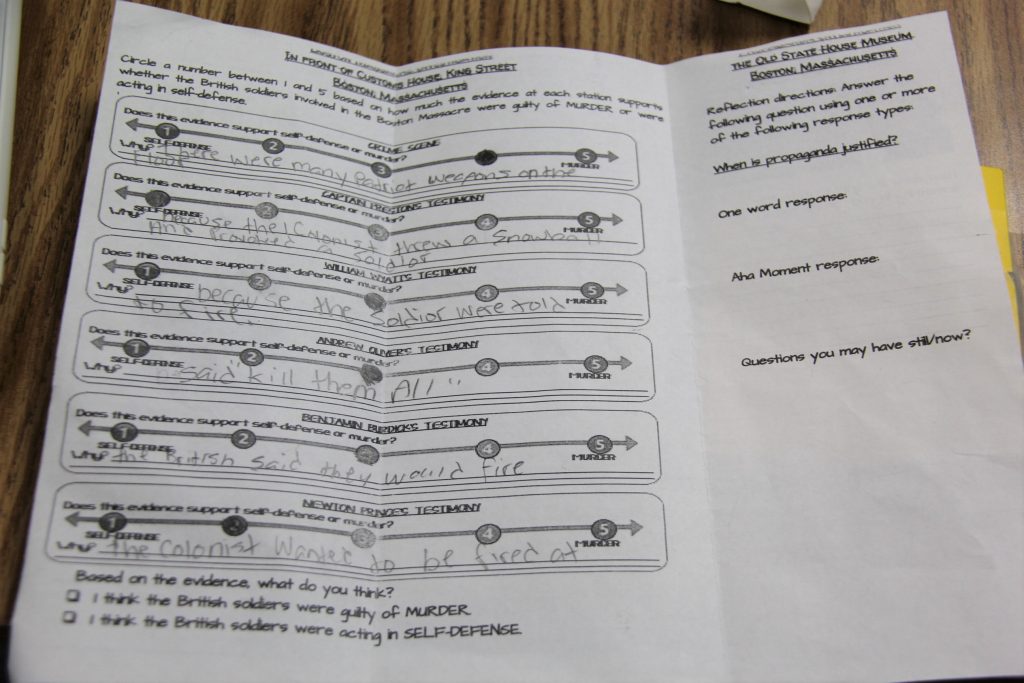

Their job was to play the role of one of four witnesses during the Boston Massacre, starting with a personal account of what occurred. After hearing the various eyewitnesses, sixth-graders filled out a questionnaire to rate from one to five whether they thought the witness accounts were evidence to support self-defense or murder – and why. This was important because the Boston Massacre eventually resulted with varying views on who was at fault when the case went to trial.

After this activity, the sixth-graders headed to other stations, all taking place in different classrooms which they rotated through in 45-minute increments.

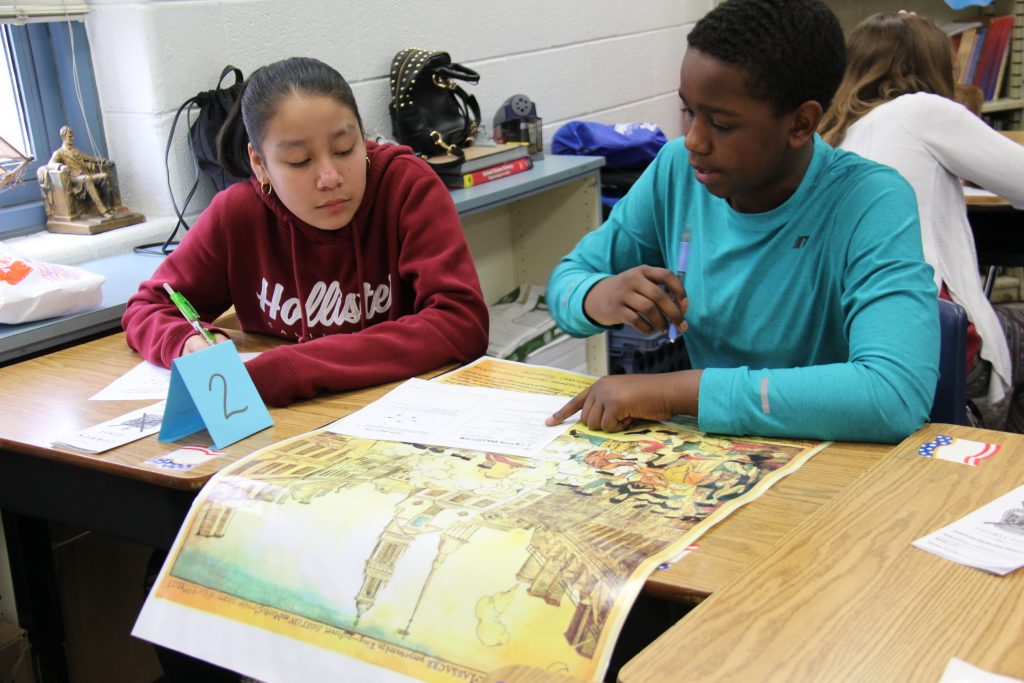

At the artifacts station, students sat in groups to review various propaganda posters or other historical items and discussed whether it was for or against the revolution.

Sixth-grader Hassan Dawson was examining one of the most famous posters used in present day in conjunction with the Boston Massacre and noticed a differentiating factor that made it a propaganda piece.

“There was more chaos,” Dawson noted. “It wasn’t really like that with each side lined up.”

At other stations, students learned about additional historical events that also contributed to revolution. Some of those stations were simulations, like the pretend tavern where they sat around with the high school students to discuss events of the time as if they were colonists.

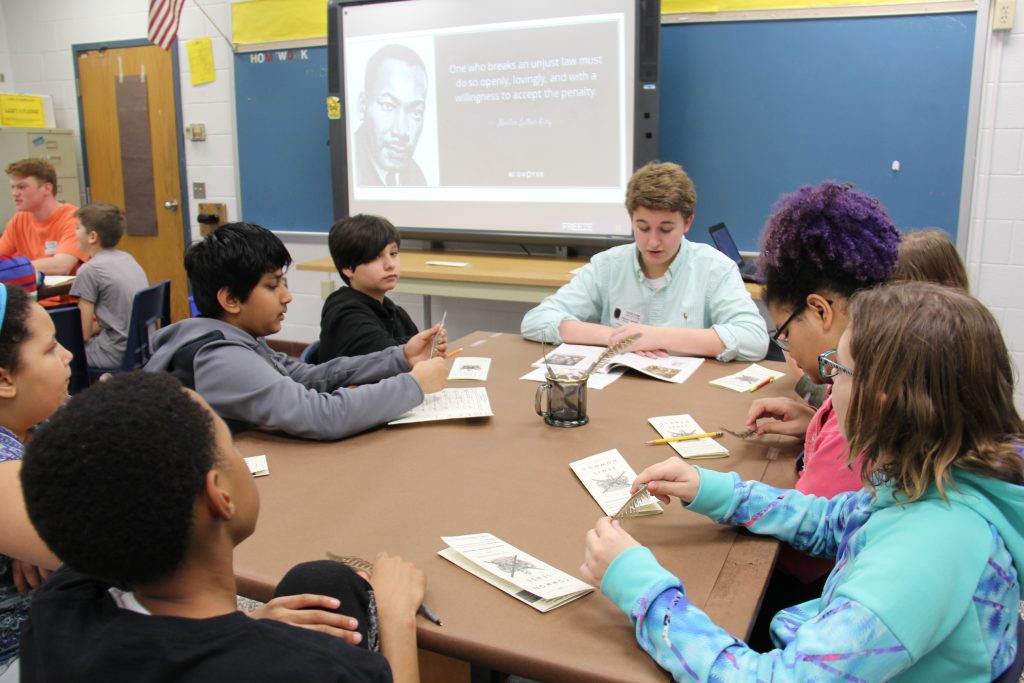

But over in room 20, a spirited debate could be heard from the hallways, and with good reason – it was a re-enactment of the First Continental Congress with students playing various delegates, debating whether the colonies should go to war with Great Britain.

“Honorable delegates,” Lee Hicks, sixth-grade social studies teacher, said in a British accent, emulating how colonists of the time spoke. “Bang on your desk and say ‘aye’ if you like what the delegate is saying, or if you don’t like, then you hiss. If it gets a bit heated as it should happen from time to time, I will have to bang the gavel and say ‘decorum delegates,’ which means to have class since you are in the Continental Congress.”

He then asked them to get into character.

“We have two key issues we must debate as a Congress. Should we oppose these Intolerable Acts passed by King George III and his parliament?” Hicks asked, which prompted pounding on desks and students to respond in emphatic ‘ayes.’

“The second is whether we should end all trade with England,” Hicks continued, a question which was met with a mix of ‘ayes’ and hisses.

The delegate from New York was the first to raise his hand.

“I highly think we shouldn’t,” the student stated, also speaking in a British accent and which everyone else similarly did.

Next, Hicks called upon “The gentleman from Virginia.”

“As far as I can see, it was the people of Massachusetts who brought these ills upon themselves, not the people of our respective colonies so why ought we take the blame for them?”

Ayes and hisses filled the room as their teacher next called upon Massachusetts.

“Are we not supposed to be acting like one nation? Are we not supposed to come together and try to defend ourselves against the injustice that Britain has put upon us?”

“Aye,” the majority of the delegates responded before the delegate from New York requested to be heard again.

“I highly disagree. We have our own states.”

The spirited debated continued for the next 40 minutes until it was time to take a vote and for students to again rotate stations. This group of sixth-graders voted to end trade with England and oppose the Intolerable Acts.

“When you make history live for students, they never forget it,” Tarkenton stated, adding that she and teachers met for months planning the stations and preparing for the day. “And, history has so many opportunities to do that. It really is about experiencing history.”